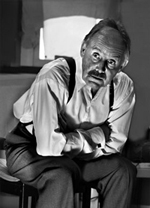

DAVID GARRICK

For over twenty years Clive Francis has been involved with David Garrick’s Temple to Shakespeare in Hampton, and for the past ten years acting as Chairman for its Trustees.

Garrick built the Temple in the riverside grounds of his magnificent villa to celebrate the genius of William Shakespeare. The Temple is open to the public on Sunday afternoons (14.00-17.00) from late March to the end of October. Admission to the Garrick Exhibition and most events is free.

Courtesy of the Garrick Club London.

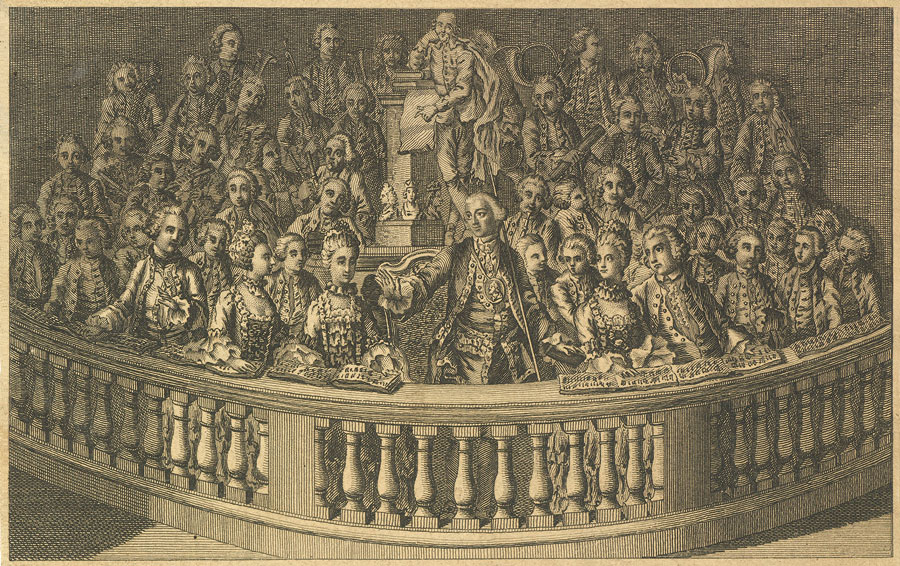

2017 was Garrick’s tercentenary and we celebrated it most royally with a variety of concerts all of which have yet to be announced. We would also like to extend a hand of acknowledgment to the Lichfield Garrick Theatre, Garrick’s home town of Lichfield.

David Garrick (1717 – 1779) was not only one the greatest actors of his day, but also a leading playwright, entrepreneur, theatre manager, copious letter writer and someone who influenced nearly all aspects of theatrical practice throughout the 18th century. He took London by storm with his portrayal of Richard III at the age of 23, bringing with it a naturalism audiences had not witnessed before. He was billed as, ‘A Gentleman who had never set foot upon the stage.’ But anonymity did not remain with him long. Very soon after his debut, Garrick made the leap to the west end, to the Theatre Royal , Drury Lane, where he eventually purchased a share of the theatre with James Lacy. Garrick's management lasted 29 years, during which time it rose to prominence as one of the leading theatres in Europe. At his death, three years after his retirement from Drury Lane and the stage, he was given a lavish public funeral at Westminster Abbey where he was laid to rest in Poets' Corner.

Useful links: www.garrickstemple.org.uk www.lichfieldgarrick.com

Much Ado about a Mulberry Tree

Clive Francis’ fascinating and humorous account of the tragicomedy surrounding the ill-fated mulberry tree which William Shakespeare planted in the garden of New Place, his home in Stratford-upon-Avon.

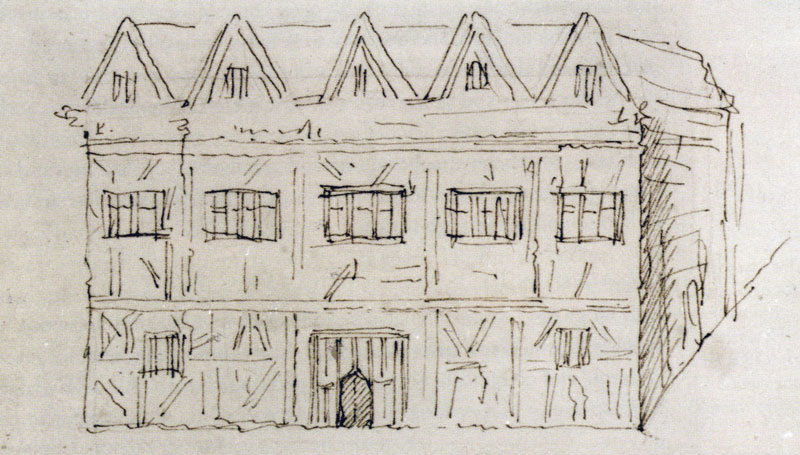

Billowing like a battered oilcloth, Macklin strutted up Chapel Lane with young Davy Garrick before him to explore Shakespeare’s magnificent home, New Place, which had proudly dominated Stratford since the reign of Henry VIII. The two actors wandered through a labyrinth of corridors and musty rooms, heavy with dust and history, and paused to look out upon a neat, manicured garden. This was indeed the main purpose of their visit, for in the centre, surrounded by a flourishing display of herbs, stood a huge, overhanging mulberry tree. Now, according to legend, King James I had encouraged the growing of this particular tree in order to promote the breeding of silkworms, and Shakespeare, like everyone else, would most certainly have obeyed the decree by the planting of a small seedling. Anyway, that is what the townsfolk wanted to believe, as the tree, like the house, had become a kind of shrine, a place of pilgrimage to the good people of Stratford-upon- Avon. Garrick was greatly impressed and, having seen all that he needed to see, returned with Macklin to London.

Then one morning in 1756 Gastrell’s patience finally exhausted itself. As yet another party tramped their muddy feet down his hall, his composure, or rather the tight-fisted serenity which he kept for these occasions, snapped, and a thin, reedy smile crept warily across his face. An idea was beginning to formalize, a plot so fiendish and brutal, so destructive and venomous in its execution that he couldn’t even communicate it to his own dear wife. Why he didn’t simply capitalize upon the situation and charge a few pence for the privilege of viewing the tree is, of course, a great mystery, for without a doubt he would have made an enormous amount, retired peacefully, and no one would have been any the wiser as to the existence of the Reverend Francis Gastrell.

But late one night, the good folk of Stratford awoke from their slumbers to the sounds of surreptitious chopping coming from the garden of New Place. Together with Mr. Ange, his faithful gardener, the mad vicar was destroying once and for all the object of his hatred. It was a fearful, chilling sound, puncturing the hearts of all that heard it. The mulberry tree, then at its full spectacular height, was being systematically and brutally flattened to the ground. The citizens stared in horror as the shadowy outline was seen to crumple and divide, before disappearing ignobly in one final splintering roar. By the following morning Shakespeare’s historic tree, that had graced his garden for over 147 years, had been reduced to nothing more than a simple pile of logs.

Thundering through the swirling mass came the post-chaise of the local magistrate, who successfully beat back the mob and managed to drive the petrified couple away and out of Stratford. A decree was put about that no one bearing the name of Gastrell would be welcome to their town again, but within two months the wretched man returned.

Opposite New Place, down a small dingy lane, lived a clock maker and his wife, one Thomas Sharp. This young man was also an experienced carpenter and silversmith, though clock making would be deemed his chief source of income, keeping them in ‘good full working order.’ Every day he would leave his little shop in Tinker’s Lane, trundle past the impressive façade of New Place and gaze despairingly at the mulberry logs still piled high in the garden. Over the months he’d watched the bark turn ashen grey and felt a ‘sincere veneration towards the memory of its celebrated planter.’

Box made by Thomas Sharp supposedly from the wood of Shakespeare’s mulberry tree. A note on the inside lid reads: ‘This box was made of the real mulberry tree planted by Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon just after it was cut down and before it was used up at the time of the [Garrick] Jubilee, when much fictitious mulberry wood supplied its place, for the purpose of memorial articles’. Photograph courtesy of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

The shop soon became known as the Mulberry Store and instantly attracted a large clientele; and as the demand for carved curios grew so Sharp’s imagination was ignited in all directions. Quickly he turned his hand to producing an assortment of cups and goblets, punch ladles, tobacco stoppers, cribbage boards, toothpick cases, nutmeg graters, ink horns, comb cases, and soon even small intricate busts of Shakespeare began to appear. As the orders expanded, the faster he had to produce, sometimes working through the night into the small wee hours.

The mood around the town was sombre and bleak, and although hostility was strongly in the air, it was contained. As Gastrell emerged from the White Lion to board his coach to Lichfield, the good citizens of Stratford, 3,000 in all, surrounded the vehicle in silent vigil and accompanied it down Sheep Street, along Waterside, over Clopton Bridge, making sure that this time he never returned to plague their town again.

And as for Thomas Sharp, well, Gastrell’s destruction soon became his fortune. He moved from the cramp surroundings of Tinker’s Lane to double-fronted premises on Chapel Street, where he and his wife settled to a life of wealth and security.

Only a few years later the town built an impressive new Town Hall, a symbol of its aspirations. In order to show its loyalty to Shakespeare it invited David Garrick to donate a statue to decorate it. To woo him, he was offered the freedom of the borough, presented in a box made of the wood of the sacred mulberry tree. Garrick ran away with the idea and created the famous three-day Jubilee in 1769. The tree itself was replaced by a cutting of the original tree, and this still stands in New Place Garden. One such cutting was given to David Garrick, which he planted in the grounds of his magnificent Villa at Hampton. It flourishes to this very day.